Michael Brill

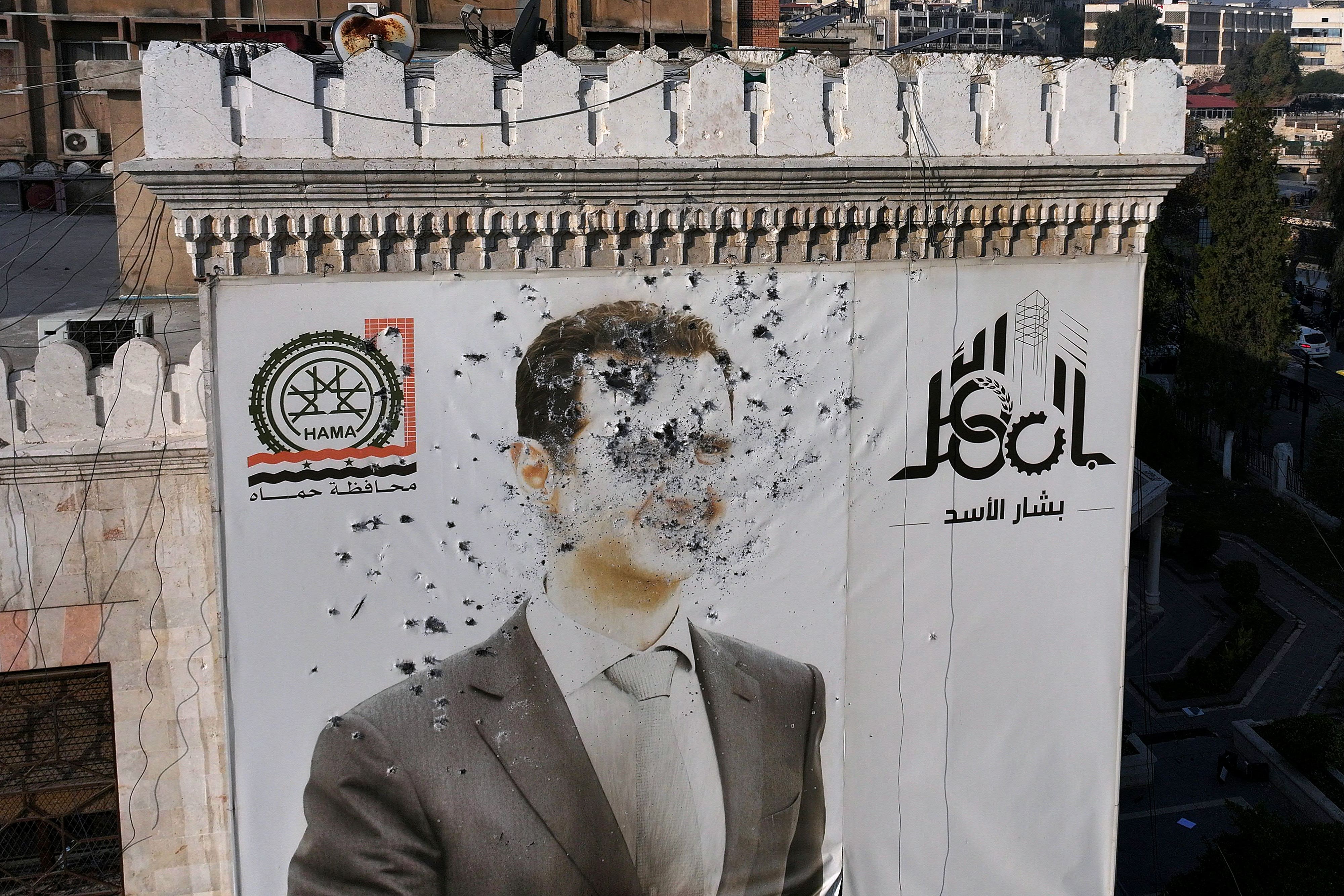

In February 2024, the History and Public Policy Program, previously at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, released the first of several batches of digitized Iraqi records. The Saddam Files collection was provided by Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Steve Coll, who obtained the records in a settlement with the Pentagon. In the early months of 2024, the collapse of Bashar al-Assad’s Baʿth Party regime in Syria and the similar availability of its own internal records to researchers by the end of the year would have seemed implausible. However, the demise of the Assad regime was an illustrative example of the Niccolo Machiavelli quote, “Wars begin when you will, but they do not end when you please.” Among the members of the “Axis of Resistance,” Syria was the only one that had an antagonistic relationship with Hamas, which had supported the Arab Spring uprising against the regime in 2011 that ultimately toppled it in December of last year. Even though Assad was no longer a friend of Hamas, Israel’s devastation of Hezbollah and Iran, combined with Russia’s focus on Ukraine, made Syria’s the weakest link of the Axis. Thus, the unexpected departure of an enduring opponent of US foreign policy in the Middle East created the greatest opportunity for US engagement in Syria in more than half a century.

Reset in the Gulf

After meeting President Ahmed al-Sharaa during his Middle East trip in May 2025, President Donald Trump directed his administration to lift longstanding sanctions on Syria in order to facilitate the country’s reconstruction after a decade and a half of war. In addition to sanctions relief, US policy can and should do more to help preserve Syria’s historical patrimony, bolster efforts to locate the missing and dead, support Syria’s transitional justice commission, and lay the legal groundwork for the future prosecution of Assad and high ranking members of his regime. Preserving the archives of the Assad regime’s political, security, and military institutions is essential for all these initiatives and more.

Along the way, the US should expand efforts to secure and digitize Assad regime documents in order to benefit US national security through a rare inside view of a former adversary. As Uğur Ümit Üngör explains, [T]he Mukhabarat archives offer an unprecedented opportunity to study the anatomy of a 21st-century authoritarian regime in the Middle East.” He adds, “This archive will yield some of the most counterintuitive yet poignant historical insights about how this regime established a veritable Gulag prison system, or tortured people en masse, or set up sectarian militias, or used chemical weapons.” Syrian civil society groups and Western-backed Non-Government Organizations (NGOs), including Commission for International Justice and Accountability (CIJA), the Syria Justice and Accountability Centre, Syrians for Truth and Justice, and the Syrian Network for Human Rights have been trying to accomplish this task for years, expanding their work on former regime documents since last December. They have the experience and expertise for scaling up these efforts with greater support for them and Syria’s interim government. Despite many differences, US experience in Iraq in handling the archives of Saddam Hussein’s regime can inform present actions in Syria, with the benefit of the support this time not coming from an occupying army. In Iraq and elsewhere, the Defense Intelligence Agency and Department of Defense contractors have digitized tens of millions of pages of documents from former adversary regimes. A glance at US-Syrian relations demonstrates why Assad regime archives should be of interest to academic researchers, intelligence and military officials, and political leaders alike.

The United States and Syria Through the Looking Glass

For several decades the United States and Ba’thist Syria drifted between engagement and confrontation in theaters across the Middle East. When Syria was a Soviet ally, President Hafez al-Assad was a subject of Secretary of State Henry Kissinger’s shuttle diplomacy to deescalate conflict with Israel. In the 1980s, US relations with Iraq under Saddam Hussein warmed due in part to their shared antagonism toward the Islamic Republic of Iran, but also its Syrian ally, described by Ronald Reagan in his diary as “the bad boy of the Middle East.” The United States and Syria subsequently clashed in Lebanon, but by the end of the decade, suddenly found themselves on the same side in a different regional conflict. Saddam’s invasion of Kuwait and the culmination of the feuding between the Syrian and Iraqi Baʿth party branches led Assad to send Syrian troops to join the US-led coalition to expel the Iraqi occupiers from the small Gulf monarchy. During the 1990s, Assad remained teasingly close yet aloof from the Arab-Israeli peace process. After the 9/11 terrorist attacks, Syria, by then under Hafez’s son Bashar, narrowly avoided inclusion in the Bush administration’s infamous “Axis of Evil” and even cooperated with the Central Intelligence Agency’s extraordinary rendition program. However, the reproachment was short-lived and the regime was later accused of supporting the armed insurgency against the US occupation of Iraq following the 2003 invasion. In 2005, following the assassination of Lebanese Prime Minister Rafiq al-Hariri, the Bush administration threw its political weight behind the Cedar Revolution and pressured Syria to withdraw its forces from Lebanon. After the outbreak of the Arab Spring in 2011, the Obama administration called on Assad to step aside, although it was ultimately the first Trump administration that struck the regime in 2017 and 2018 over its repeated use of chemical weapons.

The United States would benefit from insights afforded by official Syrian documents from each stage of this shared history, which remains incomplete. They will also yield counterfactual takeaways, such as underestimating regime resilience in 2011 and the failure to deter its chemical weapons use in 2013 and later. In addition to providing a fuller historical picture of US-Syria relations over the last several decades, the preservation and digitization of Assad regime documents will assist the US law enforcement community and its European counterparts in maintaining existing efforts to hold the perpetrators of former regime atrocities accountable. Greater attention to this issue will also benefit the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons as it works to document and eliminate Assad’s chemical weapons arsenal. In all these issues and more, there are echoes of the US experience in Iraq in 2003.

The Road to Damascus from Baghdad

The Syrian Baʿth of the Assads outlived their old rival Iraqi Baʿth of Saddam Hussein by more than two decades. Whereas Hussein was toppled by external force in the form of the 2003 US-led invasion, the Assads collapsed after its regional external supporters, Iran and Hezbollah, were distracted and degraded by the war that engulfed the Middle East after Hamas’s October 7, 2023, attack on Israel. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine reduced the direct military support it was able to provide its longstanding Assad regime ally as well.

Most policymakers and observers alike had assumed that the Assad regime brutally won its pyrrhic victory of survival in a divided Syria. However, with the benefit of hindsight, the regime can be described as collapsing gradually, then suddenly, to paraphrase Ernest Hemingway’s novel The Sun Also Rises. During the final unraveling, Syria’s rebel groups swept through the cities of the country’s heartland and into Damascus in less than two weeks, roughly half the duration of US military operations that reached Baghdad and toppled Saddam’s regime in 2003.

Despite the different geopolitical circumstances and the decades between them, one of the commonalities between the collapse of Saddam and Assad’s respective regimes was the vast quantities of administrative documents left behind. The Baʿth Party bureaucrats of both regimes documented virtually everything. Although Saddam’s regime was never fully integrated into the world of mobile phones and the internet, Assad’s produced digital and physical documents detailing their utilization and surveillance of both technologies, something Saddam’s undoubtedly would have done as well had it remained in power longer into the twenty-first century. At the same time, in the era of digital transformation, the Assad regime appears to have been technically inept in significant ways, more comfortable with its traditional systems of binders and filing cabinets than electronic databases. In both Iraq and Syria, as the regime collapsed, members of the party and security services took or burned what documents they could, although limited time and immense volume of material made the systematic destruction of archives impossible.

However, perhaps the most significant divergence between Iraq and Syria was the initial capacity of the armed groups that assumed control in the aftermath of regime collapse. In Syria, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), the largest rebel group whose leader Ahmed al-Sharaa is now the country’s interim president, fielded a force that was a small fraction of the US military troops sent to Iraq in 2003. As understaffed as that American force was, which was unable to prevent the collapse of the Iraqi state, it nevertheless had much greater manpower, along with special units dedicated to searching for and securing the archives of the former regime, capacities lacked by HTS in Syria.

The work of the Iraq Survey Group in collecting, triaging, and studying these records was a coordinated US government initiative. It enjoyed political backing from the administration of President George W. Bush due to the importance placed on finding evidence of Iraq’s reconstituted Weapons of Mass Destruction programs and ties to al-Qaeda, along with atrocities and human rights violations. The political interest in the records waned relatively quickly, although the digitized Iraqi records uploaded to the Pentagon’s Harmony Database have continued to be utilized by the US government intelligence, law enforcement, and legal communities up to the present day. Their use in human rights violation and immigration investigations is directly analogous to Syria today, where most cases relate to events that are much more recent, such as the 2024 federal indictment in California of Samir Ousman al-Sheikh, who oversaw the infamous Adra prison between 2005 and 2008.

Securing archival documents of the Assad regime was relatively low on the list of immediate priorities for HTS and Syria’s Interim government. This was especially true since the rebels exceeded their own expectations with how quickly they advanced to Damascus. Now that they are stretched thin, the realities of attempting to govern a country ravaged by nearly a decade-and-a-half of armed conflict, where some 90 percent of the remaining population live in poverty, has proven difficult. Despite the welcome news of sanctions relief and foreign investment, the resurgence of sectarian violence in various regions of Syria has only compounded Ahmed al-Sharaa’s governance challenges. Given these circumstances, a Syria Survey Group was not a realistic expectation.

Assad Regime Archives

Since 2011, NGOs and Syrian civil society groups have been at the forefront of efforts to document the atrocities of the Assad regime and its allies, along with the Islamic State and other armed groups. And beginning in 2012, CIJA, a non-profit funded by Western governments, smuggled out of Syria, indexed, and digitized some 1.1 million pages of Assad regime documents. The organization aided human rights investigations and legal proceedings against perpetrators of atrocities, even authoring a series of its own studies based on Assad regime documents, published between July and December 2023. These reports documented the Assad regime’s strategy of violently confronting the initial protests of 2011, the inner workings of the Shabiha militia, a key instrument of repression, and the siege of Homs in 2023.

The work of CIJA was still ongoing when the Assad regime collapsed in December 2024. The group was thus opportunely situated for the expanded role of securing and preserving archival documents, numbering quickly into tens of millions of pages spread across hundreds of facilities. When the Assad regime was in power, CIJA had to smuggle documents its teams obtained outside Syria for digitization and preservation.

In the chaos of the collapse of the Assad regime, United Nations officials, human rights experts, war crimes investigators, NGOs such as Amnesty International, civil society groups like the Syrian Network for Human Rights, informed observers, and scholars have all called for the preservation of official documents. All these groups value the evidence of atrocities for the purpose of chain of custody for legal proceedings. In contrast to when the Assad regime was still in power, archival preservation efforts were now also relevant for historical memory and future transitional justice initiatives. These objectives were complicated by the deliberate destruction of documents by regime personnel and the upheaval of war, along with Syrian civilians who rushed to abandoned prisons and security service facilities, hoping to find imprisoned family members alive or confirm the fate of the more than 100,000 people disappeared inside the regime’s prison system.

The First Rough Draft of History

Advances in cellphone camera technology since 2003 Iraq created more opportunities for journalists and news outlets to report on former regime documents in Syria over the last several months. Combined with the absence of a large Syrian force with the capacity to physically secure vast quantities of documents in place, journalists and private individuals were the best equipped parties for ad hoc digitization efforts in the initial weeks following the collapse of the Assad regime. Along with authoring the "first rough draft of history," journalists acquired and wrote about archival sources. In so doing, they created the outlines of potentially much larger digital archives while highlighting research subjects of interest to academic, intelligence, and law enforcement audiences.

The Washington Post wrote about surveillance and repression from Branch 322 of the General Intelligence Directorate in Aleppo; New Lines Magazine revealed Israeli-Russian mediation to curb Iran and Hezbollah’s military presence in Syria, along with the depth of Israeli telecommunications infiltration of the Assad regime; Moroccan media reported on ties between the Assad regime and the Polisario; journalists with the Jerusalem Post wrote about documents retrieved from abandoned Syrian Army border posts in the Golan; and the Sunday Times analyzed documents from four security facilities in Homs, including the Air Force Intelligence branch, reporting on Assad’s Stasi-like apparatus. Similar to 2003 Iraq, journalists had to be watchful for forged documents as well.

Other subjects to receive attention in this genre of articles were the Assad’s regime surveillance of journalists, the surveillance of Syrians living abroad in Turkey and the Gulf countries; Ahmed al-Sharaa’s file from the Palestine Branch; acrimonious relations between the Assad regime and Hamas; missing American journalist Austin Tice; the perceptions of the security services during the final rebel assault; the internal operations of Saydnaya prison, the disappearance of Christians by the regime, the placement of the children of prisoners in orphanages; Iran’s abandoned bases, the 4th Republican Guard Division commanded by Maher al-Assad; the Assad regime’s reaction to Israel’s exploding pagers attack against Hezbollah; and Iranian embassy documents on the US Marshall Plan-like ambitions the Islamic Republic had for post-war Syria.

Conclusion

On the one, hand publicizing the evil atrocities executed under the Assad regime might put Syria back into the public eye and put more pressure on Russia to extradite Assad from his current opulent living in "Russia's Beverly Hills" to justice. On the other hand, responding to the initial wave of news stories based on internal Assad regime documents, scholars cautioned that those “accessing the archives must adhere to rigorous ethical standards. They should avoid sensationalizing one of the most painful periods in Syria’s modern history or misrepresenting the content for academic gain.” And as valuable as the emerging works of journalists based on documents have been, they have been decentralized and subject to what records specific journalists and news outlets have been able to copy or take pictures of, as opposed to a coordinated research project. Together though, they highlight the need for the United States and the international community to strengthen coordinated efforts to preserve and digitize the archives of the Assad regime, to the benefit of all parties. The easiest and most practical step for doing so entails supporting the work of NGOs and Syrian civil society groups, in coordination with the interim government. In addition to the immediate considerations of securing Syria’s historical patrimony, finding the dead and missing, holding perpetrators of atrocities accountable, and facilitating transitional justice efforts, similar to the digitized archives of Saddam’s regime, Assad regime archives will likely be of interest to the US intelligence, law enforcement, and academic communities for decades to come.

Michael Brill is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of Near Eastern Studies at Princeton University, Lecturer in Middle East Studies at Smith College, and a Non-Resident Fellow at the Institute for Future Conflict. In 2024-2025, he was a Global Fellow in the History and Public Policy Program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, The views expressed in this piece are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the US Air Force, the US Department of Defense, or the US government.